Here in Europe, the memory of World War II is living, breathing, complicated beast. It was less than 100 years ago, and people remember it through stories, monuments, and plaques scattered throughout the cities of the continent. And it’s not remembered in the episodic way we in the U.S. remember the war, which for most of us distills down to we got attacked at Pearl Harbor, we beat Hitler and the Nazis (the Russians would like to have a word with you)*, and we nuked Japan. No, here in Europe it’s remembered by which of your relatives died, how much of your city was leveled, what survived, and how you remember who and what didn’t.

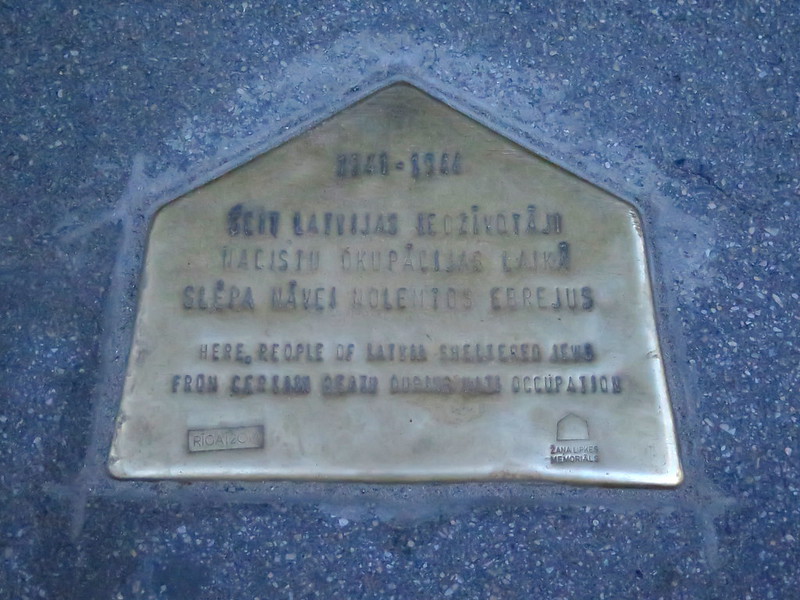

While it’s hard for me to estimate the exact number of World War II monuments, we’ve seen one in almost every place we’ve visited since we hit Russia. That includes Siberia, where there’s a Soviet monument in Ulan-Ude to the Buryats who fought in the war; to Latvia, where you can find plaques commemorating where the bombs fell and where Jewish refugees were sheltered scattered throughout the city streets; to Hungary, where towering monuments occupy city parks and the bank of the Danube River. There are places where we didn’t see World War II monuments, but in these cases we could have missed them or they could have been removed – the Soviets would have raised them in former Eastern Bloc states, and they might have fallen with the Communist governments.

The language of the monuments and plaques also varies by location; it either memorializes the loss of lives of buildings in the war generally, or it memorializes specifically the war against the Nazis. In Estonia where an estimated 1 in 4 peopled died, pamphlets tell how Estonians first fought the Soviet Union, then the Nazis to retain their independence. In Latvia and Warsaw, many of the placards say “here refugees were sheltered,” or “here bombs fell.” And then there are the scattered memorials in Bialowieza, which read (in Russian and Polish), “Here the Nazis committed terrible atrocities.”

But behind the monuments and the public face of remembrance, there’s a more complicated cultural and personal remembrance that doesn’t conform to the public memorialization. In Austria, this manifests as darkly self-critical humor scattered through the sightseeing pamphlets at hostels: “This location memorializes the terrible acts we committed. Oops, we meant the Nazis, we Austrians were just victims who were invaded.” With the fall of communism in Poland, there are whispers now that some of the murders in the forests of Bialowieza were committed by Soviet soldiers and blamed on the Nazis as a cover-up.

But this conflict of public and private remembrance is most evident in Budapest, where that recently-built “Monument to the Victims of the German Invasion” has sparked protests that the Hungarian government is ‘washing over history’ for political expedience*. An independent, home-made monument has sprouted up in front of the official memorial with personal memorabilia from victims killed by the Arrow Cross: photos, letters, ID cards, and books. It’s a reminder visitors that like the Austrians, many in Hungary welcomed the Nazis, and many murders and atrocities were committed by Hungarian hands.

Only a mile away from Budapest’s new monument, another World War II memorial sits on the bank of the Danube. Dozens of pairs of shoes, cast in bronze, are rooted into the concrete to memorialize those who were shot at the riverbank in 1944 and 1945. With the war drawing to a close and resources scarce, victims were told to remove their shoes before they were shot and their bodies tumbled into the river below. There are rumpled boots and loafers. There are fine, high-heeled pumps. There are children’s shoes.

Plaques embedded in the ground at each end state: “To the memory of the victims shot into the Danube by Arrow Cross Militiamen in 1944-45.”

—

Side notes:

* Russia took the most World War II casualties of any country by number of deaths, and they were actually the ones to take Berlin on the ground at war’s end.

**The Hungarian government of the last decade has been controlled most by Fidesz, a nationalist right-leaning party that disagrees with Germany’s policy of allowing increased immigration. The memorial cleverly furthers both of its goals by (1) de-associating guilt from itself by failing to mention the atrocities linked to the also nationalist, right-wing party of the Arrow Cross and (2) associating the crimes committed with Germany, not specifically the Nazis, which stirs up subconscious anti-German sentiment.